60 YEARS OF OUR CONSTITUTION : THE ROAD AHEAD

By Justice Parvat Rao, Hyderabad:-

Though our Constitution was adopted on 26th November, 1949, it commenced fully on 26th January, 1950. How our Constitution came to be framed and how it evolved during this period will be a timely study now that 60 years will be completed by 26th January, 2010.

The Background:

Deliberations for the British leaving India started soon after the Second World War ended in 1945. Clement Attlee became the Prime Minister of England on 16th July, 1945 with the Labour party winning the election. The Cabinet Mission plan of 16th May, 1946 initiated the steps for the formation of the Constituent Assembly for drawing the Constitution of India rejecting the claim of the Muslim League for a separate sovereign State of Pakistan though no agreement for United India could be reached. M.A. Jinnah advocated the two nation theory in his Presidential address at the Lahore session of the Muslim League on 23rd March, 1940 itself on the following thesis:

“They (Islam and Hinduism) are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but are, in fact, different and distinct social orders, and it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality, and this misconception of one Indian nation has gone far beyond the limits… The Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, literatures…..they belong to two different civilizations which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions. Their outlooks on life and of life are different…. To yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority, must lead to growing discontent and final destruction……”

The Congress was yet hoping that they would agree for United India presumably, on the basis that most of the Muslims were converted Hindus.

The Cabinet Mission, in order to avoid delay in the formulation of a new Constitution, adopted a practical course of utilizing the then recently elected Provincial Legislative Assemblies in British India as the electing bodies for election of members of the Constituent Assembly. Each Provincial Legislative Assembly was to elect a specified number of representatives-each part of the Legislative Assembly (General, Muslim or Sikh) electing its own representatives by the method of proportional representation with single transferable vote. Provinces were divided into three sections: Section A included Madras, Bombay, United Provinces, Bihar, Central Provinces and Orissa; Section B included Punjab, North West Frontier Province and Sind; and Section C including Bengal and Assam. The total number of members for British India was fixed at 292 and the Princely Indian States were to choose a maximum of 93 members-the selection by them had to be determined by consultation. The election of the members from the Provinces in British India was held in July, 1946 and thereafter the Constituent Assembly was summoned on 9th December, 1946. The Muslim League started direct action demanding for Pakistan on 16th August, 1946 itself; and on learning about the summoning of the Constituent Assembly on 9th December, Jinnah gave a statement that no representative of the Muslim League would participate in the Constituent Assembly. In the first session of the Constituent Assembly of India on 17th December 1946, when the resolution ‘in the nature of pledge’ relating to Aims and Objects of the Constitution to be drafted was being considered, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar observed:

“I know today we are divided politically, socially and economically. We are a group of warring camps and I may go even to the extent of confessing that I am probably one of the leaders of such a camp. But, Sir, with all this, I am quite convinced that given time and circumstances nothing in the world will prevent this country from becoming one. With all our castes and creeds, I have not the slightest hesitation that we shall in some form be a united people. I have no hesitation in saying that notwithstanding the agitation of the Muslim League for the partition of India some day enough light would dawn upon the Muslims themselves and they too will begin to think that a United India is better even for them”.

On 22nd January, 1947 the Constituent Assembly adopted the resolution regarding Aims and Objects unanimously. Some of the Aims and Objects are:

“(1) This Constituent Assembly declares its firm and solemn resolve to proclaim India as an Independent Sovereign Republic and to draw up for her future governance a Constitution;

xxx xxx xxx

(4) WHEREIN all power and authority of the Sovereign Independent India, its constituent parts and organs of government, are derived from the people; and

(5) WHEREIN shall be guaranteed and secured to all the people of India justice, social, economic, and political; equality of status, of opportunity, and before the law; freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, worship, vocation, association and action, subject to law and public morality; and

(6) WHEREIN adequate safeguards shall be provided for minorities, backward and tribal areas, and depressed and other backward classes; and

(7) WHEREBY shall be maintained the integrity of the territory of the Republic and its sovereign rights on land, sea and air according to justice and the law of civilized nations; and

(8) this ancient land attain its rightful and honoured place in the world and make its full and willing contribution to the promotion of world peace and the welfare or mankind”.

As the Muslim League stuck to its demand for a separate Muslim nation, on 3rd June, 1947 a plan was finally settled and the British Cabinet announced that Partition of India would be made according to that plan. As per that plan Bengal and Punjab Legislative Assemblies decided to join the new Constituent Assembly to be formed for Pakistan. The non-muslim majority areas in Bengal decided for partition and that West Bengal should join the existing Constituent Assembly; and non-muslim majority areas in Punjab decided in favour of partition and for joining the existing Constituent Assembly. Sind, North West Frontier Provinces, Beluchistan and Sylhet (In Assam) decided to join Pakistan. Thereafter the British Parliament enacted the Indian Independence Act on 18th July, 1947 under which two independent dominions of India and Pakistan were constituted with effect from 15th August, 1947. The Act also gave full power on the Constituent Assembly of each dominion to frame and adopt respective Constitutions and to supersede the Indian Independence Act.

Before the midnight of August 14th/15th , the Constituent Assembly of India held the historic meeting when at the stroke of midnight hour India i.e., Bharat woke up to freedom and the Constituent Assembly assumed full sovereign powers for the governance of India. President of the Assembly, Dr. Rajendra Prasad in his address at that meeting before that midnight hour prophesied: “India has a great part to play in the shaping and moulding of the future of a War-distracted World”, even while expressing his sorrow “that the country which was made by God and Nature to be one stands divided today”. He assured:

“To all the minorities in India we give the assurance that they will receive fair and just treatment and there will be no discrimination in any form against them. Their religion, their culture and their language are safe and they will enjoy all the rights and privileges of citizenship, and will be expected in their turn to render loyalty to the country in which they live and to its constitution. To all we give the assurance that it will be our endeavour to end poverty and squalor and its companions, hunger and disease; to abolish distinctions and exploitation and to ensure decent conditions of living”.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru in his memorable ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech moved the resolution for all members of the Constituent Assembly to take the following pledge after the last stroke of the midnight:

“At this solemn moment when the people of India, through suffering and sacrifice, have secured freedom, I……….. do dedicate myself in all humility to the service of India and her people to the end that this ancient land attain her rightful place in the world and make her full and willing contribution to the promotion of world peace and the welfare of mankind”.

He elaborated:

“That future is not one of ease or resting but of incessant striving so that we might fulfill the pledges we have so often taken and the one we shall take today. The service of India means the service of the millions who suffer. It means the ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity. The ambition of the greatest man of our generation has been to wipe every tear from every eye. That may be beyond us but as long as there are tears and suffering, so long our work will not be over.

And so we have to labour and to work and work hard to give reality to our dreams. Those dreams are for India, but they are also for the world, for all the nations and peoples are too closely knit together today for any one of them to imagine that it can live apart.”

Dr.Radhakrishnan was the only other member who spoke before that midnight. While pointing out the weaknesses, he also warned about the dangers ahead if the people failed in their responsibilities and in correcting themselves, and called for self examination. He exhorted:

“Should we not now correct our national faults of character, our domestic despotism, our intolerance which has assumed the different forms of obscurantism, of narrow-mindedness, of superstitious bigotry? Others were able to play on our weakness because we had them. I would like therefore to take this opportunity to call for self-examination, for a searching of hearts. We have gained but we have not gained in the manner we wished to gain and if we have not done so, the responsibility is our own. And when this pledge says that we have to serve our country, we can best serve our country by removing these fundamental defects which have prevented us from gaining the objective of a free and united India…………..

Our opportunities are great but let me warn you that when power outstrips ability, we will fall on evil days. We should develop competence and ability which would help us to utilize the opportunities which are now open to us. From tomorrow morning – from midnight today – we cannot throw the blame on the Britisher. We have to assume the responsibility ourselves for what we do. A free India will be judged by the way in which it will serve the interests of the common man in the matter of food, clothing, shelter and the social services. Unless we destroy corruption in high places, root out every trace of nepotism, love of power, profiteering and black-marketing which have spoiled the good name of this great country in recent times, we will not be able to raise the standards of efficiency in administration as well as in the production and distribution of the necessary goods of life.

That was the background for the framing of our Constitution. The Aims and Objects adopted by the Constituent Assembly virtually got reflected in the Preamble to the Constitution.

The First Decades -Jawaharlal Nehru:

During these 60 years, our Constitution did not remain the same; it underwent many changes both by amendments and also because of the changing content given to its various provisions by interpretation by the Constitutional Courts-mainly the Supreme Court. There were as many as 94 amendments to the Constitution, the last being on 12th June, 2006. During the first two decades, most of the amendments related to securing the Constitutional validity of Zamindary Abolition Laws, Land Reform Laws, restrictions on property rights State’s power of compulsory acquisition and requisitioning of private property. The Constitution (1st Amendment) Act was enacted on 18th June, 1951. It amended Articles 15 and 19, among others, and inserted Articles 31A and 31B and Schedule -9. This amendment was made by the Constituent Assembly itself which was continuing then as Union Legislature after the Commencement of the Constitution.

During the first decade after independence, the problems faced by the country were diverse and critical. Immediately after the partition and the formation of the two Nations there were wholesale migrations of population: Hindus from Pakistan to Bharat and Muslims from Bharat to Pakistan. There were talks about exchange of populations. Jinnah was agreeable and Patel was inclined, but Gandhi and Nehru did not agree. The communal disturbances which started with the direct action call of Jinnah continued even after partition. It was not known how democracy with adult franchise would work in a country afflicted by illiteracy, unemployment and poverty. [Now the age for voting rights was reduced from 21 to 18 years by the 61st Amendment Act of 28th March, 1989] The country mainly depended on agricultural and there were no industries to talk about. Most of the people lived in villages and communications were inadequate. There was the Jammu and Kashmir problem and within a month after independence in the guise of tribes, Pakistans army marched into Jammu and Kashmir in a bid to make it a part of Pakistan and they succeeded in part – the problem is continuing as a festering sore even today. The society itself was fractured with regional, caste and class differences. There were the neglected Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to be attended and relieved from untouchability and accepted as equals in every respect. Untouchability was abolished on paper but it still continues to a degree and will continue till it is erased totally from the hearts and minds of all sections of the people including the Scheduled Castes.

Fortunately the problem of Princely States was settled by the indefatigable effort of Sardar Vallabhai Patel. Only Jammu and Kashmir remains a problem – if only Patel had his way that would not have been there. In the Privy Purses case Chief Justice Hidayatullah described how the territories of the Princely States became part of Bharath: 216 princely states merged in the adjoining provinces ; 61 princely states were converted into centrally administered areas ; and 275 princely states formed Unions and signed instruments of accession; only three retained there integrity – Hyderabad, Mysore and Jammu and Kashmir. He also observed that the Indian princely states covered about 48% of the area of the Indian dominion and their total population was 28% of the total population of the dominion. The regional and linguistic feelings subsided apparently with the re-organization of the states mostly on linguistic basis and abolition of class A, B, C and D States in 1956 and subsequently also.

Providentially there was no break in the governance because more than half a decade of the freedom struggle brought out eminent men as great and popular leaders of the nation who gave inspiration and direction to the nation to start with and to continue with the governance and face new problems. There was no military rule at any time unlike in the neighboring countries. However, emergency was declared under Article 352 during the wars started by Pakistan and China; and President’s rule was imposed in some States from time to time under Article 356.

Personal laws applicable to ‘Hindus’ were codified and made uniform in the fifties. Reservations were provided for the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Backward Classes and Other Backward Classes in Government employment and in educational institutions run by the government or with government support and are being continued with vigour (76th Amendment Act was enacted on 31st August, 1994 to enable continuation of 69% reservation in Tamilnadu by including the relevant Act under the 9th Schedule; 77th Amendment of 17th June 1995 to protect reservation to SC/ST employees in promotions; 81st Amendment of 9th June, 2000 to protect SC/ST reservations in filling backlog of vacancies; 82nd Amendment of 8th September, 2000 to permit relaxation of qualifying marks and other criteria in reservation and in promotion for SC/ST candidates; 85th Amendment of 4th January, 2002 to protect seniority in case of promotions of SC/ST employees; and 93rd Amendment of 20th January, 2006 to enable provision of reservation for OBC’s in Government as well as Private Educational Institutions. The 77th, 81st , 82nd and 85th Amendment Acts have been upheld in M.Nagaraj vs Union Of India [ 2006 (8) SCC 212]. In Ashoka Kumar Thakur vs Union Of India [ 2008 (6) SCC 1] the 93rd Amendment Act has been upheld so far it relates to the State maintained institutions and aided educational institutions, but as regard private unaided educational institutions the question has been left open by the majority with Bhandari, J holding that it is invalid in its application to them). By the 65th Amendment of 12th March, 1992 National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes was formed with specified statutory powers and by 89th Amendment of 28th September, 2003 separate National Commissions-one for Schedule Castes and another Scheduled Tribes-were formed by bifurcation; and Article 338 was suitably amended and a new Article 338A was inserted. Reservation for SC/ST and nomination of Anglo-Indian members in Parliament and State Assemblies was extended from time to time by 10 years each time by the 8th, 23rd, 45th, 62nd, and 79th Amendments, from the original 10 years to 60 years i.e., up to 2010. The economic progress and industrialization through five years plans took shape.

The Congress led by Nehru dominated during the fifties and the big question was ‘After Nehru Who?’ Nehru’s dream of ‘China India bhai bhai’ and peace were shattered by China suddenly attacking India in October 1962 and capturing several posts in NEFA even while holding India’s hand and singing Panchasheel. Unfortunately Nehru did not foresee this even when China blatantly occupied Tibet in 1950 and crushed the Tibetan revolt against the Chinese occupied forces in 1959 and immediately started fortifying it militarily. The question of who after Nehru, was resolved when Lal Bahadur Shastri became Prime Minister after Nehru and after him Indira Gandhi.

Nehru was Prime Minister from 15th August, 1947 to 27th May, 1964. After him Lal Bahadur Shastri was Prime Minister for 1 ½ years; and after his sudden demise Indira Gandhi was the next Prime Minister from 24-1-1966 and continued till she was defeated in 1977. Thus from 1950 till 1977, Congress was in power for nearly 27 years continuously; and, in all, nearly 46 years till now.

Indira Gandhi – Emergency:

It was during the seven years of seventies when Indira Gandhi was in power that India faced the first and only threat to its democracy and the people faced threat to their freedoms when she imposed Emergencies.

Indira Gandhi was the choice of a coterie of elder leaders of the day called ‘Syndicate’ led by Kamaraj. Her selection was questioned by Morarji Desai and he contested for the leadership of Congress Parliamentary party. In a secret ballot election Indira Gandhi won overwhelmingly and became prime minister in January 1966. Gradually she started asserting her self. In the fourth general elections held in February 1967 for Parliament and the States, though the Congress won in Parliamentary elections with much reduced majority, it lost in eight major States and in most of the States the Coalition governments were formed by non congress parties. The climax came when President Zakir Hussain died in 1969. The syndicate opted for N. Sanjeeva Reddy for presdentship and made Indira Gandhi propose him. There after she set up V.V. Giri for predentship and got him elected and he became President in August 1969. This led to a split in Congress for the first time into Congress(O) led by the Syndicate and Congress (R) led by Indira Gandhi. There after she fully asserted herself and started personal rule with no holds barred.

Meanwhile on 19th July, 1969 an Ordinance was promulgated nationalizing fourteen named commercial banks the deposits of which exceeded Rs.50 crores each and corresponding new Nationalised banks were established. This Ordinance was questioned by way of Writ Petitions under Article 32 before the Supreme Court. Thereafter on 9th August, 1969 the Ordinance was replaced by an Act, bringing it into force retrospectively from the date of the Ordinance. The Writ Petitions were heard by a Bench of eleven Judges. The Act was struck down by a majority of ten Judges with Ray, J dissenting, on 10th February, 1970 (R.C.Cooper vs. Union of India 1970 (1) SCC 248).

On 6th September, 1970 the President issued orders in respect of each of the Rulers of former Indian States directing that with immediate effect they would cease to be recognized as Rulers to their respective States, in purported exercise of the powers vested under Article 366(22) of the Constitution which resulted in the stoppage of payment of their privy purses and the continuance of their personal privileges. This was questioned by some of the Rulers under Article 32 by way of Writ Petitions and they were heard by a eleven Judges Bench of the Supreme Court. By judgment dated 15th December, 1970 a majority of nine Judges (with Mitter and Ray JJ. Dissenting) allowed those Writ Petitions and the orders of the President derecognizing the Rulers, were held to be illegal and inoperative (Madhava Rao Scindia vs. Union of India 1971 (1) SCC 85). It was contended on behalf of the Union of India that in issuing the impugned orders the President exercised his political power in the nature of sovereign power and therefore they could not be questioned in a Court of Law. The majority held that there was no sovereign or political power in the executive and that our Constitution recognized only three powers – the legislative, the judicial and the executive powers and that in our country the legal sovereignty vested with the Constitution and the political sovereignty with the people and that the executive possessed no sovereignty. It is interesting to note that the procedure of the President passing orders in respect of each of the Rulers derecognizing them was adopted after the Constitution (24th Amendment) Bill, 1970 for omitting Articles 291, 362 and 366 (22) relating to privy purses, and rights and privileges of Rulers of Indian States, failed to receive the requisite majority in the Rajya Sabha.

On 27th December, 1970 the Lok Sabha was dissolved one year and two months ahead and mid-term elections (the 5th General Election) were held in March, 1971 and Congress (R) led by Indira Gandhi won 360 seats out of 518 and continued to be in power with two thirds majority. Thereafter by Constitution (26th Amendment) Act, 1971 (enacted on 28-12-1971) the privy purses were abolished.

Earlier, Constitution (24th Amendment) Act was enacted on 5th November, 1971 amending Articles 13 and 368 enabling the Parliament to amend the fundamental rights and making ineffective the decision of the Supreme Court in Golak Nath (AIR 1967 SC 1643) wherein a nine Judges Bench of the Supreme Court held by a majority of six that Constitution Amendment Acts also would be attracted by Article 13 and that therefore they would have to be consistent with the provisions of Part III. The 24th Amendment Act along with the 25th (restricting property rights and compensation for acquisition of property, by amending article 31, 26th and 29th (placing land reform Acts and amendments to these Acts in Schedule) Amendment Acts were questioned in several Writ Petitions under Article 32 and they were heard by a thirteen Judges Bench of the Supreme Court. By judgment dated 24th April, 1973 the Supreme Court partly allowed those Writ Petitions (Kesavananda Bharathi Vs. State of Kerala 1973 (4) SCC 225). The Supreme Court disagreed with the view taken in Golak Nath as regards the interpretation of the expression ‘law’ in Article 13 of the Constitution, and the majority held that the enactments under Article 368 were in exercise of the Constituent power and that therefore they were not attracted by Article 13. The view of the majority signed by nine Judges is: decision in Golak Nath is not correct; Article 368 does not enable Parliament to alter the basic structure or frame work of the Constitution; the 24th Amendment is valid; Clauses (a) and (b) of Section 2 of the 25th Amendment are valid ; the first part of Section 3 of the 25th Amendment is valid but the second part, namely, “and no law containing a declaration that it is for giving effect to such policy shall be called in question in any court on the ground that it does not give effect to such policy” is invalid; the 29th Amendment is valid; the validity of the 26th Amendment should be determined by the Constitutional bench in accordance with law. By an innovative and far reaching construction of Article 368, reading the Constitution as a whole, the Supreme Court for the first time enunciated the basic structure/features concept of the Constitution and held that the amending power of the Parliament under that Article did not extend to altering the basic structure or features of the Constitution. What falls within the basic structure/features has to be decided by the Constitutional Courts. Thus Kesavananda Bharathi has given a new direction to the nation in Constitutional Governance – the inalienable Dharma of the Constitution concerning governance and Constitutionalism has been laid. By virtue of this decision whatever falls within the basic features of our Constitution cannot be amended under Article 368 of the Constitution. In Minerva Mills Ltd vs Union of India [1980 (3) SCC 625] a five Judges Bench of the Supreme Court has held (by a majority of four Judges) that a limited amending power is one of the basic features of our Constitution and that therefore the limitations of that power cannot be destroyed and that: “Parts III and IV together constitute the core of commitment to social revolution and they, together, are the conscience of the Constitution is to be traced to a deep understanding of the scheme of the Indian Constitution…….To give absolute primacy to one over the other is to disturb the harmony of the Constitution. This harmony and balance between fundamental rights and directive principles is an essential feature of the basic structure of the Constitution.” and that, “Three Articles of our Constitution, and only three, stand between the heaven of freedom into which Tagore wanted his country to awake and the abyss of unrestrained power. They are Articles 14, 19 and 21.”

In I.R.Coelho vs. State of Tamilnadu [2007 (2) SCC 1] a nine Judges Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously has held that all Constitutional amendments made on or after 24th April, 1973 (date of the judgment in Kesavananda Bharathi) by which Schedule-9 was amended shall have to be tested on the touchstone of basic structure doctrine and any law placed in Schedule 9 has to satisfy that doctrine because laws included in Schedule 9 do not become part of the Constitution. The nine Judges Bench also referred with approval to the following observations of a five Judges Bench in its unanimous judgment in M.Nagaraj vs. Union of India [2006(8) SCC 212]:

“It is a fallacy to regard fundamental rights as a gift from the State to its citizens. Individuals possess basic human rights independently of any Constitution by reason of the basic fact that they are members of the human race. These fundamental rights are important as they possess intrinsic value. Part III of the Constitution does not confer fundamental rights. It confirms their existence and gives them protection……A right becomes a fundamental right because it has foundational value……After three decades, the Supreme Court overruled its previous decision in A.K. Gopalan and held in its landmark judgment in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India that the procedure contemplated by Article 21 must answer the test of reasonableness. The Court further held that the procedure should also be in conformity with the principles of natural justice. This example is given to demonstrate an instance of expansive interpretation of a fundamental right. The expression ‘life’ in Article 21 does not connote merely physical or animal existence. The right to life includes right to live with human dignity”.

The nine Judges Bench also observed: “The principle of constitutionalism is now a legal principle which requires control over the exercise of governmental power to ensure that it does not destroy the democratic principles upon which it is based. These democratic principles include the protection of fundamental rights. The principle of constitutionalism advocates a check and balance model of the separation of powers; it requires a diffusion of powers, necessitating different independent centres of decision-making”.

After the Judgment of Kesavanada Bharathi was delivered on 24-4-1973, when Chief Justice S.M.Sikri retired on 25-4-1973, three senior most judges of the Supreme Court were over looked ( JM Shelat, KS Hegde and AM Grover JJ)and they resigned on 30-4-1973. After Justice H.R. Khanna gave his famous dissenting Judgment on 28th April, 1976 in ADM Jabalpur Vs. Shivakant Shukla [1976(2) SCC 521], even though he was the senior most puisne Judge , he was also overlooked when Chief Justice A.N.Ray retired on 28-1-1977. That was the time when the Congress in power wanted committed Judges, committed not to the constitution but to the policies of the ruling party.

Due to the dictatorial governance of Indira Gandhi and the ruthless manner in which the people were suppressed and due to deteriorating economy with food shortages and rising prices, there was widespread unrest; there were major agitations mainly in Gujrat and Bihar. Loknaik Jaipraksh Narayan took leadership of Bihar agitation and under his inspiration a country wide movement was started in which Sri Morarji Desai and several eminent personalities joined from various walks of life.

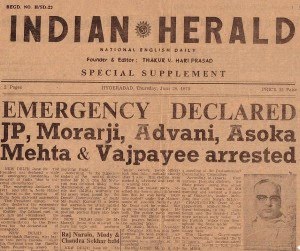

On 12th June, 1975 the Allahabad High Court delivered judgment invalidating the election of Smt Indira Gandhi to the Parliament. Then internal emergency was declared on 25th June, 1975 even when the national emergency which was proclaimed on 3rd December, 1971 when the Indo-Pakistan war broke out, was kept continuing even after the war was over. Even before the emergency came into effect, midnight arrests began and all the leaders including JP, Morarji Desai and Jan Sangh Party Leaders including A.B. Vajpayee and L.K. Advani were arrested in the preceding night. These arrests continued for several days and several RSS swayamsevaks and elders were arrested.

During the pendency of her appeal in the Supreme Court, Parliament passed the Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 1975 amending the Election Laws retrospectively which in effect validated her election. Thereafter on 10th August, 1975 the 39th Amendment Act was enacted substituting Article 71 by a new Article 71, and amending Article 329, and inserting Article 329A, and included certain enactments in the 9th Schedule. The new Article 71 took election disputes relating to election of President and Vice President out of the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and enabled the Parliament to make law in respect of the same. The new Article 329A provided for special provisions in respect of election for Parliament in the case of Prime Minister and Speaker and Article 329 was amended making it subject to Article 329A. This was obviously with a view to get over the judgment of Allahabad High Court invalidating her election. After this 42nd Amendment Act was enacted on 18-12-1976 amending a number of articles and inserting several articles.

General elections were declared in March 1977 and Internal Emergency was lifted. Even before that, Janata Party was formed on 23rd January, 1977 under the guidance of Shri Loknayak Jayaprakash Narain. After this, Shri Jagjeevan Ram and several other eminent personalities joined opposing Indira Gandhi. Mammoth meetings were held under their leadership through out the country and people were aroused .In the 6th general election Congress (I) was defeated, Smt Indira Gandhi herself losing the election-this was the first time that Congress lost power. Shri Morarji Desai became the fourth Prime Minister on 24th March, 1977.

The Janata government withdrew National Emergency on 27th March, 1977. The 43rd and 44th Amendment Acts were enacted on 13-4-1978 and 30-4-1979 respectively repealing the objectionable amendments made by the 39th and 42nd Amendment Acts and also providing for human rights safeguards and mechanisms to prevent the abuse of executive and legislative authority. Some of the amendments made by the 42nd Amendment Act were retained–like the insertion of Part IV A, Clause (f) in Article 39, Article 39A, Article 43A, Article 48A etc.

The defeat of Smt Indira Gandhi in 1977 when she was in full power and even though two emergencies were in force, established the potential of our people and the resilience of democracy even in extreme adversity. It was providential that she decided to test herself in a general election and that Lok Nayak and other eminent leaders could join and give lead to defeat her. She brought down by a political gimmick of successfully enticing Shri Charan Singh to come out of Janata government and take over as Prime Minister only to bring him down after 23 days; and this led to dissolution of Lok Sabha by President Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy on his own without exploring any alternatives. In the 7th general election Smt Indira Gandhi rebounded back to power as Prime Minister with a thumping majority. Congress rule under her continued till her assassination on 31-10-1984 and immediately Rajiv Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister. He continued till 1-12-1989. It was during this period that the judiciary was subordinated and filled with yes-men. Even permanent posts came to be filed with additional judges for a period of two or three years which was being extended at the will of the political executive. Judges were being transferred at the will of political executive.

The Judiciary:

There was a period of uncertainty from 2-12-1989 to 21-6-1991 when Shri P.V. Narsimha Rao came to power and continued for almost 5 years. And then again there was uncertainty from 16-5-1996 to 18-3-1998. All this was a period of coalition governments with no Prime Minister having a firm voice as in the past with Shri Jawaharlal Nehru and Smt Indira Gandhi at the helm. It was in this uncertain period that the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association and Others vs. Union of India [1993 (4) SCC 441] came up before the Supreme Court by way of a public interest litigation (PIL) seeking directions for filling up vacancies of judges in the Supreme Court and High Courts. As the earlier decision in S.P. Gupta’s case (1981 Supp SCC 87) was questioned and doubted it finally came up for hearing before a nine Judges Bench and was decided on 6-10-1993. A majority of seven judges (A.M.Ahmadi and M.M.Punchhi JJ dissenting) has held that the opinion of the Chief Justice of India(CJI) has primacy in the matter of all appointments of judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts reversing the decision in S.P.Gupta’s case. Subsequently on President’s Reference in Special Reference No.1 of 1998, Re [1998 (7) SCC 739] the Supreme Court held that consultation with CJI implied consultation with a plurality of judges in the formation of opinion of the CJI. After these judgments the appointment of the judges of the High Court became the responsibility of the Supreme Court and the High Courts.

There are instances which establish that recommendations were made for appointment as judges of High Courts and even of Supreme Court without full verification of the antecedents, qualifications and character of the persons recommended. There is the case of Shri K.N. Srivastava. His name was cleared for appointment as permanent judge of Gauhati High Court by the Chief Minister of Mizoram, Governor of Mizoram and Chief Justice of Gauhati High Court, Government of India and Chief Justice of India on the basis that he was a judicial officer and was qualified to be so appointed. A warrant dtd. 15th October, 1991 was also issued by the President for his appointment as permanent judge . At that stage a Writ Petition was filed in Gauhati High Court by an advocate questioning his selection on the ground that he was not qualified for such appointment. By the time the matter came up for admission, the warrant of appointment of Srivastava was already received by the High Court. After noticing the points raised by the petitioners the Division Bench of the High Court observed that it was doubtful that Srivastava was qualified and restrained him from taking the oath until further orders. Srivastava filed Special Leave Petition before the Supreme Court against the order of the High Court and also for transfer of the matter to the Supreme Court. The matter was finally heard by a three Judges Bench of the Supreme Court (Sri Kumar Padma Prasad vs Union of India 1992 (2) SCC 428) The writ petition was allowed holding that Srivastava was not qualified to be appointed as a judge of the High Court as he did not hold any judicial office observing:

“It is for the first time in the post-independent era that this Court is seized of a situation where it has to perform the painful duty of determining the eligibility of a person who has been appointed a Judge of High court by the President of India and who is awaiting to enter upon his office……We are at a loss to understand as to how the bio-data of Srivastava escaped the scrutiny of the authorities…..A cursory look at the bio-data would have disclosed that Srivastava was not qualified…..Needless to say that the independence, efficiency and integrity of the judiciary can only be maintained by selecting the best persons in accordance with the procedure provided under the Constitution. These objectives enshrined under the Constitution of India cannot be achieved unless the functionaries accountable for making appointments act with meticulous care and utmost responsibility”.

There was also the case of Justice V. Ramaswamy who became judge of the Supreme Court in October, 1989 and on allegations of financial improprieties and irregularities while he was Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court, motion for his removal was moved in the Lok Sabha for removing him from office which was admitted. The Speaker of the Lok Sabha constituted a Committee under Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 and the report was also submitted by the Committee. It is another matter that the Congress party decided to abstain from voting, with the result the motion did not get the requisite majority . Then there is the case of Chief Justice A.M.Bhattacharjee who was forced to resign on an agitation by the Bar Council of Maharashtra and Goa, Bombay Bar Association and the Advocate’s Association of Western India on the alleged ground that he was being paid a disproportionate royalty for overseas publication rights of his two books. The question as to how Advocates should deal with such issues without affecting judicial independence was considered in a public interest litigation under Article 32 in C.Ravichandran Iyer vs. Justice A.M. Bhattacharjee [1995 (5) SCC 457]. There are also the cases of Justice Soumitra Sen of Calcutta High Court elevated as permanent judge in December, 2003 and Chief Justice P.D.Dinakaran of Karnataka High Court (made Chief Justice of that Court from 8th August, 2008)- proceedings for their removal are pending consideration in the Parliament.

The method of appointment devised by the Supreme Court on an extended interpretation of the Constitutional provisions is under debate and the matter is of great importance because of pre-eminent position of the Constitutional Courts. Already a debate has been initiated by two senior and eminent advocates of the Supreme Court, Shri Anil Divan and Shri T.R. Andhyarugina by their centre page articles in the Hindu of 17th and 18th December, 2009. Earlier in 2008 Sri Anil Divan said“ the final word in appointments to the higher judiciary can never be safely entrusted to fractious coalition government–weak on governance, soft on terrorism and high on corruption. Each coalition partner will demand quotas on High Bench as well as the High Courts-on occasions threatening withdrawal of support. An increasing politicization of judges indebted to political factions is not a result ‘devoutly to be wished’”. Though he now suggests a separate commission referring to reforms which took place in UK and South Africa, Sri T.R.Andhyarugina wisely questions“ Would such commissions be successful in India? There are justifiable doubts about finding independent and competent members who would not be influenced in their decisions. This raises the vexed question whether the present system with suitable modifications should be continued or judicial commissions be introduced in India.”

The reforms in the judiciary are already taking place and some more are on the anvil. A totally inadequate judicial strength is sought to be rectified- the number of puisne judges of the Supreme Court Judges has already been increased to 30 from 25. Recently the Chief Justice of India pointed out that 35,000 subordinate courts would be needed to tackle the pendency and the new cases, and that though 16,000 subordinate courts are sanctioned at present only 14,000 are functional. The law minister announced that he would be introducing the Judges (Standard and Accountability) Bill in the Parliament soon. At the recent meeting of the Chief Ministers and the Chief Justices in August 2009, it was agreed in principle that an All India Judicial Service should be created and that before giving effect to its formation comprehensive deliberations should be held. In view of the fact that all the large and medium States are having National Law Universities it would be necessary to set up such a service without any delay to attract talent to the judiciary. Justice Krishna Iyer has suggested that what is required is not merely increase in number of courts but also attracting the ablest and training them. Filling up of vacancies has also to be streamlined to avoid inordinate delays. The National Law University, Delhi has started a post graduate diploma course on judging and court management designed to meet the needs of law graduates who are interested in entering the judiciary. Other National Law Universities also can start such diploma courses. National Judicial Academies also have been started in many States. Under the circumstances it not impossible for higher judiciary to be provided with the necessary infrastructure to facilitate proper selection of candidates for appointment as High Court Judges and Supreme Court Judges after through enquiry of their antecedents, character integrity, ability, independence and commitment to the judiciary. If All India Judicial Services is set up, recruitment from the cadre of district judges to the High Court can be increased up to even 60 percent or more. How transparency and openness in the selection process can be achieved has to be widely debated

Secularism under our Constitution :

In S.R. Bommai and Others vs. Union of India [1994(3) SCC 1] a nine Judges Bench of the Supreme Court has held that secularism is part of the basic structure of the Constitution and that it meant religious tolerance and equal treatment of all religions. Sawant and Kuldip Singh, JJ, with Pandian J concurring, held as follows:

“When the State allows citizens to practice and profess their religions, it does not either explicitly or implicitly allow them to introduce religion into non-religious and secular activities of the State. The freedom and tolerance of religion is only to the extent of permitting pursuit of spiritual life which is different from the secular life. The latter falls in the exclusive domain of the affairs of the State”.

In M.P.Gopalakrishnan Nair vs. State of Kerala [2005(11) SCC 45] a two Judges Bench of the Supreme Court has held that it is now well settled that:

“(i) Constitution prohibits the establishment of a theocratic State;

(ii) State is not only prohibited to establish any religion of its own but is also prohibited to identify itself with or favouring any particular religion;

(iii) The secularism under the Indian Constitution does not mean constitution of an atheist society but it merely means equal status of all religions without any preference in favour of or discrimination against any one of them.”

In Aruna Roy vs. Union of India [2002(7) SCC 368] it was contended that teaching Sanskrit to school children is against secularism. A three Judges Bench has held in that case that teaching of Sanskrit as an optional subject does not offend secularism. Shah J observed:

“None can also dispute that the past five decades have witnessed a constant erosion of the essential social, moral and spiritual values and increase in cynicism at all levels. We are heading for a materialistic society disregarding the entire value-based social system. None can also dispute that in a secular society, moral values are of utmost importance. A society where there are no moral values, there would neither be social order nor secularism. Bereft of moral values secular society or democracy may not survive. As observed by the committee, values are virtues in an individual and if these values deteriorate, it will hasten or accelerate the breakdown of the family, society and the nation as a whole.”

xxx xxx xxx xxx

“….Further are we trying to promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood among all people of India believing in different religions? It appears that we have not taken necessary steps for such a purpose. Similarly, uptil now instead of protecting and improving the natural environment, we have damaged it. There is widespread deforestation; lakes are being used for constructing buildings and we are losing compassion for living creatures including human beings. Why is that so? Let it be discussed by experts. May be that basics of all religions may help in achieving the objects behind fundamental duties.”

Xxx xxx xxx xxx

Dharmadhikari, J. in his separate Judgment observed as follows:

“….. The lives of Indian people have been enriched by integration of various religions and that is the strength of this nation. Whatever kind of people came to India either for shelter or as aggressors, India has tried to accept the best part of their religions. As a result, a composite culture gradually developed in India and enriched the lives of Indians. This happened in India because of the capacity of Indians to assimilate the thoughts of different religions. This process should continue for the betterment of a multi-religious society which is India.

In a pluralistic society like India which accepts secularism as the basic ideology to govern its secular activities, education can include study based on ‘religious pluralism’. ‘Religious pluralism’ is opposed to exclusivism and encourages inclusivism.”

“…..The attainment of constitutional ideals is possible only if side by side with sharpening intellect, the moral character of children, is also developed to make them good citizens.”

“…Democracy cannot survive and the Constitution cannot work unless Indian citizens are not only learned and intelligent, but they are also of moral character and imbibe the inherent virtues of the human being such as truth, love and compassion”

Education under our Constitution:

In Unni Krishnan vs. State of A.P [1993(1) SCC 645] a five Judges Bench of the Supreme Court has held that right to education is a fundamental right and that it is implicit and flows from the right to life guaranteed under Article 21. Construing Article 21 in the light of Articles 41, 45 and 46 it has been held that every child citizen upto the age of 14 years has fundamental right to free education. Subsequently by 86th Amendment Act of 12th January, 2002 Article 21A was inserted in Part III providing that “the State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of 6 to 14 years in such manner as a State may by law determine” and also added an additional fundamental duty in Article 51A as follows: “(k) who is a parent or guardian to provide opportunities for education to his child or, as the case may be, ward between the age of 6 and 14 years”. In Avinash Mehrotra vs. Union of India [2009(6) SCC 398] a two Judges Bench of the Supreme Court has held:

“Education today remains liberation-a tool for the betterment of our civil institutions, the protection of our civil liberties, and the path to an informed and questioning citizenry. Then as now, we recognize education’s “transcendental importance” in the lives of individuals and in the very survival of our Constitution and Republic.

Education remains essential to the life of the individual, as much as health and dignity, and the State must provide it, comprehensively and completely, in order to satisfy its highest duty to citizens.”

The court also held that “in view of the importance of Article 21A, it is imperative that the education which is provided to children in the primary schools should be in the environment of safety”. In that case (PIL) the petitioner prayed for a direction to bring about safer school conditions. He narrated how a fire in a school in Kumbakonam District in Tamilnadu killed more than 90 children. The school building had a thatched roof with a single entrance and a narrow stair case with windowless classrooms and housed more than 900 students. The ventilation was also very poor. The fire from the kitchen in the building caused the thatched roof to catch fire and it fell on the children. Safety measures were totally neglected. The court gave notices to all the States and directed them to provide information about the condition of the schools and what precautions were being taken to see that the schools had proper and safe accommodation. The matter is pending in the Supreme Court.

Though fundamental right in article 21A required the State to provide free and compulsory education to all the children in 2002 itself, comprehensive steps have not yet been taken in this regard by the States or the Union-now education is in the concurrent list. An educated, informed and dedicated citizenry with character is a must for the proper functioning of the institutions under our Constitution, and will form a strong foundation for our democracy.

Minorities and Uniform Civil Court:

In Bal Patil vs. Union of India [2005 (6) SCC 690] a three Judges Bench of the Supreme Court traced the history of the struggle for Independence and the need for engrafting Articles 25 to 30 in the Constitution and observed:

“The minorities initially recognized were based on religion and on a national level e.g. Muslims, Christians, Anglo-Indians and Parsis. Muslims constituted the largest religious minority because the Mughal period of rule in India was the longest followed by the British Rule during which many Indians had adopted Muslim and Christian religions.

Ideal of a democratic society, which has adopted right to equality as its fundamental creed, should be elimination of majority and minority and so-called forward and backward classes. The Constitution has accepted one common citizen ship for every Indian regardless of his religion, language, culture or faith. The only qualification for citizenship is a person’s birth in India. We have to develop such enlightened citizenship where each citizen of whatever religion or language is more concerned about his duties and responsibilities to protect rights of the other group than asserting his own rights. The constitutional goal is to develop citizenship in which everyone enjoys full fundamental freedoms of religion, faith and worship and no one is apprehensive of encroachment of his rights by others in minority or majority.

The constitutional ideal, which can be gathered from the group of articles in the Constitution under the chapters of fundamental rights and fundamental duties, is to create social conditions where there remains no necessity to shield or protect rights of a minority or majority.

Hindu society being based on caste, is itself divided into various minority groups. Each caste claims to be separate from the other. In a caste-ridden Indian society, no section or distinct group of people can claim to be in majority. All are minorities amongst Hindus.

It is unfortunate that though Article 44 in Part IV (Directive Principles of State Policy) requires that the State shall endeavour to secure for its citizens a uniform civil code through out the territory of India, no effort has been made in that directions in these 60 years and even to prepare the Muslim citizens towards that, even though Dr. Tahir Mohmmed in his book ‘Muslim Personal Law’ observed “in pursuance of the goal of secularism, the State must stop administering religion based personal laws.” He further appealed to the Muslim community:

“Instead of wasting their energies in exerting theological and political pressure in order to secure an “immunity” for their traditional personal law from the State’s legislative jurisdiction, the Muslims will do well to begin exploring and demonstrating how the true Islamic laws, purged of their time-worn and anachronistic interpretations, can enrich the common civil code of India.”

Chief Justice Chandrachud in Mohd. Ahmed Khan vs. Shah Bano Begum [1985(2) SCC 556] pointed out in his Judgment speaking for the five Judges Bench that it was unfortunate that there was no official activity for framing a common civil code for the country and observed: “We understand the difficulties involved in bringing persons of different faiths and persuasions on a common platform. But, a beginning has to be made if the Constitution is to have any meaning…it is beyond the endurance of sensitive minds to allow injustice to be suffered when it is so palpable.”

In John Vallamatton vs. Union of India [2003(6)SCC 611] Chief Justice V. N. K hare in his judgment observed:

“Before I part with the case, I would like to state that Article 44 provides that the State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India. The aforesaid provision is based on the premise that there is no necessary connection between religions and personal law in civilized society. Article 25 of the Constitution confers freedom of conscience and freedom to profess, practice and propagation of religion. The aforesaid two provisions viz. Articles 25 and 44 show that the former guarantees religious freedom whereas the latter divests religion from social relations and personal law. It is no matter of doubt that marriage, succession and the like matters of a secular character cannot be brought within the guarantee enshrined under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution…In Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India it was held that marriage, succession and like matters of secular character cannot be brought within the guarantee enshrined under Articles 25 and 26 of the constitution. It is a matter of regret that Article 44 of the Constitution has not been given effect to…A common civil code will help the cause of national integration by removing the contradictions based on the ideologies.”

Kuldeep Singh, J. emphatically expressed in Sarla Mudugal’s case (1995 (3) SCC 635) as follows:

“Those who preferred to remain in India after the partition, fully knew that the Indian leaders did not believe in two nation theory, or three nation theory and that in the Indian Republic there was to be only one nation- Indian nation- and no community could claim to remain a separate entity on the basis of religion.”

The interpretations of the constitutional provisions by the Supreme Court become part of the Constitution. Constitution achieves fulfillment through its institutions and institutions function through their personnel. We find a gradual deterioration in the functioning of the legislatures including parliament and executive. Recently it was brought out that the number of parliamentary sittings has come down from an average 140 a year in the past to 102 in 1988 and 74 sittings in 2004. Even those sittings do not transact much work and no purposeful debates are allowed because of the uproars created and adjournments which has become very common now and even important Bills are passed without any debate. The executive has also become weak and ineffective. Politics has become a business and source of ill gotten income running into thousands of crores. Though these are becoming more common and obvious as recent happenings in AP and Karnataka have shown. There is no popular uproar or resentment. There are no corrective measures in sight. Abuse of rural employment and other welfare schemes have become so common that people accept them without even a whimper. Ultimately it is the society which has to awaken itself and take up this stupendous task of correcting the malise. Let us hope that during the coming decades we will be able to realise the hopes and dreams of the framers of the Constitution – of what they expressed on that midnight when Bharat gained Swaraj. Akhila Bharatiya Adhivakta Parishad should take the lead in this direction by awaking and educating the people. (http://www.adhivaktaparishad.org/?p=100)