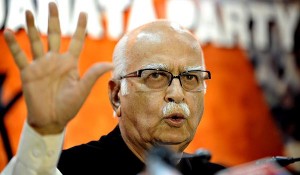

LK ADVANI

Last week (June 16) Shri Ahmad Tariq Karim, High Commissioner for Bangladesh in New Delhi, met me at my residence and had a very enlightening discussion with me on Bangladesh-India-Pakistan relations.

When we parted company that day I presented him a copy of “My Country, My Life”, my autobiography, and he promised to send me some of his own writings on the issues we had discussed.

His letter to me from the High Commission has been a fulsome expression of gratitude. In this letter he refers to my autobiography and comments: “As I am going through it, I find it an invaluable insight into the history of our common sub-continent”.

Also enclosed with this above-mentioned letter are several publications carrying articles by the High Commissioner who has already retired from the State’s Foreign Service but who has been asked to continue in his present post until the present Indian Government is there. In the sheaf of publications sent there is a 19-page pamphlet authored by him which bears the titled “PAKISTAN: Stalking Armageddon?”

In this pamphlet, the Bangladeshi leader says:

Pakistan which in its obsession with matching India tit-for-tat in the missiles and nuclear race, has failed to address more fundamental problems related to societal development within its own orders, and has gone pretty nigh bankrupt in the process. There seems to be a growing perception, including among many Pakistanis themselves, that the country is launched on the trajectory to a self-destructive implosion.

Contrasting India’s approach to politics and governance with that of Pakistan the Bangladesh High Commissioner writes in his pamphlet:

“While the Indian leadership, despite the conflict with Pakistan, chose the path of democracy and invested in strengthening their democratic and civic institutions, the political leadership of Pakistan used Kashmir as the reason for embarking on the road to authoritarian governance. Ironically, in the process they sowed the seeds for their own displacement by the very institution that was normally meant to be the guardian of their security. The armed standoff over Kashmir was inevitably enlarged by the military into a permanent security threat to the newly established Muslim nation.”

Under heading “Pakistan’s Seven Deadly Sins,” Mr. Karim sums up his assessment of the consequences of Pakistan’s myopia thus

In a sense, the singular short-sightedness of successive central leadership that governed Pakistan from its very birth, and the several layers of illusions that it had cocooned itself into, inevitably led it into its third, most disastrous, war with India in 1971. Despite its humiliating defeat at the hands of India in 1971, Pakistan appears to have clung on tenaciously to these illusions right up to its last localized, but brutal, conflict with India on the Kargil heights in Kashmir in 1999. The illusions, which may be described as Pakistan’sseven deadly sins, were:

1. The doctrine of Islamic invincibility over the infidel Hindus: Pakistan being the epitome of an Islamic State, each Pakistani warrior could easily take on ten soldiers of the infidel Hindus, who had no stomach for a fight.

2. The doctrine of West Pakistani superiority over the inferior Bengalis: The Bengalis of East Pakistan belonged to an inferior class, and its leadership were in collusion with the Hindu Indians, and therefore not to be trusted.

3. The doctrine of its indispensability as a strategic ally of the US to the exclusion of all other factors: The US, through its defense cooperation agreements with Pakistan, would come to Pakistan’s aid militarily in the event of any armed conflict with India, even after Pakistan had withdrawn from CENTO and SEATO. Unfortunately, successive US administrations shied away from bluntly telling successive Pakistani regimes the truth; the US military cooperation with Pakistan did not, ipso facto, imply in any manner that the US would also join on Pakistan’s side in the latter’s conflict with India.

4. The China card: China, having fought a war with India, and being an adversary of the Soviet Union in the rivalry between the two for leadership of the Communist world, was Pakistan’s natural ally.

Immediately after China normalized relations with India, it sent a very clear message to the other South Asian countries: while it was not going to abandon them, it was in their interest to mend fences with India. The Chinese also made it clear that China should not be factored in by any one of them in their conflicts or stand-offs with India. Nepal and Bangladesh absorbed this friendly advice relatively, quickly, but Pakistan either chose to ignore it or completely misread it.

5. The Iran card: Pakistan had forged strong relations with Iran ever since its independence. Its ties with Iran were founded on a shared culture, religion and geographical contiguity. Iran also had been a co-partner with Pakistan in the US-led CENTO alliance, as well as the Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD), a tri-partite social and economic alliance between Iran, Pakistan and Turkey.

Iran, too, shares China’s misgivings about provoking outsiders to intervene in the region. Iran does not want to be drawn into a conflict in South Asia. On the contrary, it views India as a vast potential market, conveniently nearby, for selling its oil and gas, and as a window to the advanced technology that it yearns for, and is irked by Pakistan’s perceived role as a spoiler in its efforts to engage India in a pipeline deal.

6. A belief that the majority of the people of Kashmir want to join Pakistan: Pakistan has tenaciously clung on to the belief that the vast majority of the people of the Valley wish to join Pakistan, and that it is only India’s intransigence that is preventing this.

7. The defence of East Pakistan lay in the plains of the Punjab

However, when put to the test in 1971 when East Pakistan was the major theatre of war, China kept its distance from the fray, although it did supply Pakistan with hardware replenishments to its own profit, and even indulged in some shadow-boxing with India along India’s north-eastern borders as it had done earlier during the 1965 war.

In 1965, however, the main theatre of the war was in the west. In 1971, both the Chinese and the Americans while supporting the unity of Pakistan, were critical of the Yahya Khan regime’s heavy-handedness in addressing an essentially political problem with a military solution which left the Pakistan Army’s Eastern Command fighting not only the enemy without, but also the enemy within: a notional home-base of which the entire people was totally hostile to it

In totality this pamphlet adds up to a very perceptive summing up of all that has gone wrong with Pakistan in the three score years since its foundation. In the preamble to this pamphlet Ahmad Tariq Karim warns that “the selfish corporate mindset of the Pakistan military establishment ultimately may lead to a nuclear confrontation with India.”

Karim concludes the pamphlet with a powerful plea made to the international community in general and to SAARC in particular to deploy measures that would encourage the return of democracy to Pakistan as soon as possible.

L.K. Advani

New Delhi

June 22, 2012